Last updated on January 15, 2019

At first glance, the house at 197 Green Street is unique for its small size and the colorful graffiti that has covered its exterior since 2016 — the result of collaboration between the owner and real estate developer City Realty Group and artists. City Realty Group is currently awaiting approval from the city to demolish the now-vacant house and build a four-story, mixed-use development.

But if we look behind its 1950’s siding, and comb the historical record, we discover that the house is not, as it might first appear, an outdated structure. Rather, the house represents a significant period of time in the development of Jamaica Plain, and of Green Street in particular. 197 Green Street is likely the last remaining building on the east end of Green Street that was built at the start of the neighborhood’s transition from a rural landscape of farms and country estates to both a suburb for commuters and a home for middle-class residents who also worked locally. When it was built, the population in the area was sparse; less than 50 years later, it was booming.

In the 18th century, Jamaica Plain was a rural village in the Town of Roxbury. Its wooded hills and 120-acre pond made the area “a perfect site for the country estates of the well-to-do,” wrote the Jamaica Plain Historical Task Force. In addition to farmland and the small-scale industry that developed along Jamaica Pond and the Stony Brook, the neighborhood attracted a “small but choice circle of elegant, graceful and cultivated people used to wealth and accomplished in the arts of life,” the task force wrote.

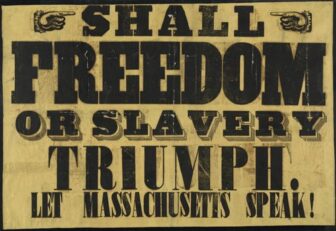

The Boston and Providence Railroad lines extended into the neighborhood in 1834, followed by the introduction of the horse-car trolley in 1856, and the creation of electric streetcar service in 1889. “At the same time, a flood of popular mid-19th-century magazines and books extolled the morality and healthfulness of living in the country and the joy of connecting to nature and your own piece of land (McAlester, 2017).” The availability of public transportation and a desire for a rural lifestyle led many in the middle-class to escape the crowded and dirty city of Boston at the end of the workday for the charms of a home in the Jamaica Plain countryside.

What was once a predominantly agricultural and genteel community had become a “streetcar suburb” for middle-class commuters (Stiles, 2001).

This new commuter class drove a demand for housing. The large estates owned by the wealthy residents of Jamaica Plain were soon split up into lots and sold off to developers and homeowners, including the estates along Green Street. Multiple houses were now being built on land where once only a single family had lived. However, as Stiles explains, the lots on Green Street served more than just the needs of the new commuter class. They also provided land on which to build homes for middle-class residents who lived and worked locally, such as artisans, gardeners, and teachers.

The house at 197 Green Street was very likely one of these early homes. Based on historical plans and maps, and the architecture of the house, it was probably built sometime between 1854 and 1858. As we will see, this would place the construction of the house immediately after the initial subdivision of the eastern end of Green Street, but before the area saw a rapid increase in population and industry brought on by electric streetcar service.

Typical of the architectural styles of the mid-nineteenth century, 197 Green Street is an Italianate Cottage with Greek Revival details. The wood framed house would have originally been covered in clapboard siding. Because there were few formally trained architects in America at the time, the house was likely built by a housewright who drew on pattern books for its design. (1) Specifically, the layout of the house resembles the Italianate design “A Suburban Cottage for a Small Family” from Andrew Jackson Downing’s popular 1842 “Cottage Residences” pattern book.

As Downing explains:

“…this cottage, with its moderate accommodations and small lot of ground, may be made productive of a considerable degree of interest and beauty, as well as comfort and enjoyment. There is nothing in the plan of the house or garden, that may not be realized by a family living upon a very small income, provided the members of the family are persons of some taste and refinement…”

Remarkably, 197 Green Street today sits on approximately the same-sized lot of land on which it was originally built and retains its original use as a single-family home. It also retains original details like the classic molding and entablature around the front door, and its sidelights, which are now painted over. An 1888 Sanborn Fire Insurance map indicates that the property formerly included a three-bay, one-and-a-half story barn in the rear. However, the barn was demolished in 1943 due to the deterioration of its foundation.

Now let’s take a deep dive into the origins of this historic structure, and by extension, the history of the neighborhood.

We begin our story in 1836 when farms and large estates still dominated Jamaica Plain. Samuel Griswold Goodrich, world-famous children’s author, was facing sudden financial troubles (Goodrich, 1898). Without the means to maintain his Jamaica Plain “Rockland” estate, Goodrich, known to his readers as Peter Parley, sold his family mansion and subdivided his 38 acres of land into 32 lots (Stiles, 2001). These lots were located along what would become the western section of Green Street, west of the Stony Brook and closer to Centre Street. Trustees then sold these lots to multiple buyers for development.

“The development of residential and commercial lots along Green Street was…one of the first speculative real estate ventures in an area that would see a tremendous increase in such activity within a few decades.” (Stiles, 2001)

Concurrently, Goodrich financed the laying of a new street through his property, as well as his neighbors’ property, that of Betsy and Able Green. This new street was one of the first to connect Jamaica Plain’s two main roads, Centre Street and the Norfolk and Bristol Turnpike (now Washington Street) (Stiles, 2001). The newly laid street was named “Willow Street” on Alexander Wadsworth’s 1836 plan of lots on Goodrich’s land. [2]

On August 14, 1837, Willow Street was renamed “Green Street,” most likely to honor Betsy and Abel Green. A deed from 1846 conveying the Greens` land mentions that a portion of their land had “been taken for Green Street.” The owners of the land adjacent to the Greens’, from whom the Greens had bought their land in 1834, were Betsy’s brothers, Samuel and Daniel Jackson. The Greens would continue to live on Green Street until 1846, at which time they moved to Salisbury and then Amesbury, MA, leaving behind their family name on a prominent road.

The same year that Goodrich drew up plans to construct Green Street, Abel, a gardener and picture frame maker, and Betsy Green sold three-quarters of an acre of their land to Henry Newman. Newman was a resident of Boston who already owned adjacent land along the new street. The property that the Greens sold appears to just be a slip of land that ran along the southwest side of the planned street, beside land that would eventually become the lot for 197 Green Street. Perhaps the Greens sold this land because the new street had separated it from the remainder of their property.

In 1842, Henry Newman sold eleven acres of his land along Green Street to an attorney and real estate agent named Henry Codman. This land was situated east of the Stony Brook, on the southwest side of Green Street surrounding Union Avenue, and included the small bit of land conveyed to Newman by the Greens six years prior. With the introduction of Codman to our story, we will learn how the land at, and adjacent to, 197 Green Street was utilized prior to the construction of the house.

Henry Codman was born on October 1, 1789, in Portland, Maine. In 1808, Codman graduated from Harvard College and was later admitted to the Suffolk Bar (Massachusetts Historical Society, 2008). For 38 years, he practiced as an attorney at his office on State Street in Boston. After marrying Catherine Willard Amory in 1821, he began managing the family’s real estate business, which he inherited from his father-in-law, John Amory (Mass Historical Society, 2008). Codman managed a number of properties in Boston, which he rented out to tenants.

One of Codman’s more significant properties was Amory Hall in the Downtown Crossing area of Boston. Codman built the three-story granite building in 1835 at the corner of West and Washington Streets. The building was comprised of three stores, five offices, and two large halls for public meetings (Dearborn, 1851). The Hall functioned as a rental space for events and exhibitions. In 1903, the Amory-Codman family leased Amory Hall to George A. Carpenter for a term of 60 years. Carpenter, in turn, demolished the Hall, and, in 1905, constructed a six-story building that still remains at that site (National Register, 2014). Today you will find a sign over the front door with the words “Amory Building,” homage to the property’s previous owners.

In 1837, after living for four years across from the Boston Common on Tremont Street, the Codmans moved into their mansion house, which was located on a farm on School Street in Roxbury. Their 62-acre farm had horses, milking cows, pigs and oxen, and land that cultivated many types of fruits and vegetables.

In 1842, Codman purchased Newman’s land along Green Street, which was less than half a mile down the street from his School Street farm. On September 19, 1842, shortly after buying Newman’s land, Codman commenced the construction of a cottage. He built the cottage with the intent to lease it, and two to three acres of land, to his gardener of at least nine years, George Belford. (3) The land included a garden and pasture for Belford to tend to. In November, Belford, a native of Ireland, moved into the cottage in exchange for $10 a month in rent.

On January 25, 1852, Codman hired John Minchin, also a native of Ireland, to take the place of Belford as his gardener. That November, Minchin moved into the cottage where Belford had lived, and began taking care of the farm, garden, and grounds. The following year Belford would die of a tumor at the age of 47.

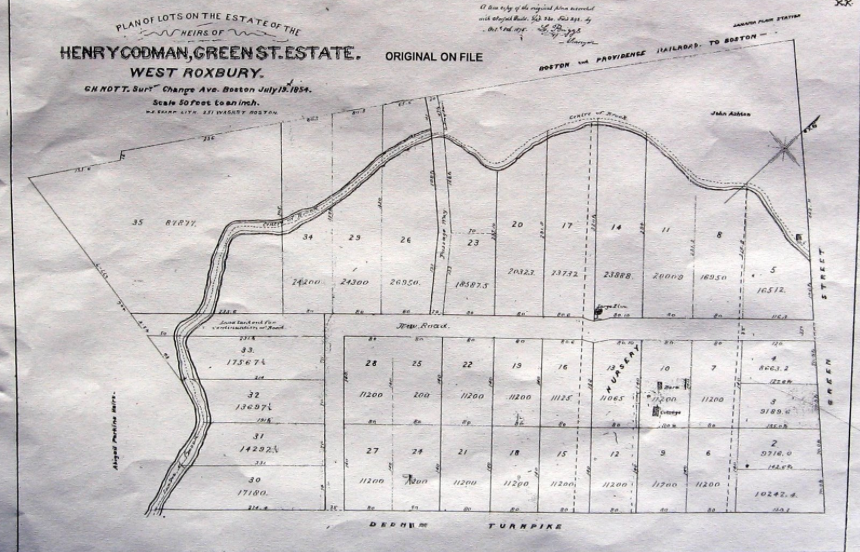

In 1853, Codman succumbed to “dropsy,” or edema. The next year his heirs subdivided his Green Street land into lots and sold them at public auction. It is interesting to note that Belford and Minchin’s cottage can be seen on G.H. Nott’s plan of lots on Codman’s estate, along with the gardeners’ barn and nursery.

On September 21, 1854, the Boston Daily Atlas advertised the auction, touting the lots’ access to public transportation and location in the country:

“Will be sold at public auction, thirty-four House Lots, varying in contents from nine thousand to twenty-five thousand feet, and one of eighty-seven thousand feet and upwards, at Jamaica Plain, bounding on Green Street and Norfolk and Bristol turnpike; and within three minutes walk of Green street station, on the Boston and Providence Railroad, where trains stop several times a day.

The lots are beautifully situated in a quiet healthy locality within convenient distance of schools and churches, in the vicinity of an excellent neighborhood, and but ten minutes distance from the city by railroad.

They constitute a portion of the estate of the late Henry Codman, Esq., and offer a rare opportunity to persons desiring to build in the country.” (Bulger, 2008)

That year, Codman’s heirs conveyed three lots of land (lots 1, 2, and 3 on Nott’s plan) to William M. Shute for $331. 197 Green Street would eventually be built on Lot #3, and Shute its first owner. An 1858 map of Jamaica Plain indicates that the owner of a structure on Lot #3 was “W.M. Shute,” suggesting that 197 Green Street was built by Mr. Shute sometime between 1854 and 1858.

William M. Shute was born in 1804 in Concord, New Hampshire. In 1832 he married Martha Chaplin in Rowley, MA, and together they had six children. The Shutes began their married life in Alabama, where they lived until 1838. The following year they moved to Boston, where Shute opened his hat and fur shop, William M. Shute & Son, at 173-175 Washington Street in Downtown Crossing. His son Judson eventually worked at the store as a clerk and took over the business in 1871 after his father’s death.

In addition to running his shop in Boston, Shute purchased property in Jamaica Plain. In 1846, Shute bought land from Charles McIntier at the corner of Washington and Green Streets, possibly the land that had been owned by the Greens. Between 1853 and 1854, Shute and two of his associates bought and sold land along Greenough Street. Then, in 1854, Shute acquired the future site of 197 Green Street and two adjacent lots from the Codman family. The Shutes likely never lived at 197 Green Street, but rather rented out the house while living in Boston on Davis Street and later West Brookline Street.

We, unfortunately, cannot identify the first occupants of the house under Shute’s ownership. Reliable documentation regarding the residents of Jamaica Plain prior to West Roxbury’s annexation to Boston in 1874 is no longer in existence. Also, fire insurance maps and residential atlases that cover the Jamaica Plain area are not available prior to 1874, except for one 1858 residential map. We can, however, identify the first time that 197 Green Street is owner-occupied, with the purchase of the house by Mary Starr.

197 Green Street remained in William Shute’s possession until April 1868, at which time he sold the house to Starr, wife of William H. Starr. In the subsequent months, Shute would sell his other two Codman lots, perhaps due to failing health. Shute would die two years later in Boston from heart disease, at the age of 66.

William Henry Starr was born in 1822 in Connecticut. (4) Starr married Mary Maria Sprague and together they had two children, Ida W. and Forest. In 1867, William Starr entered into an agreement with Alden Bartlett to lease land at the corner of Green Street and Union Avenue, where Hotel Morse now sits. Bartlett allowed Starr to construct two buildings on this land in order to operate a blacksmith, wheelwright, or paint shop. The following year, Starr’s wife purchased 197 Green Street, which was conveniently located two doors down from Starr’s shop. The Starrs would become the first owners of 197 Green Street to also live in the house.

In 1879, at the end of his lease with Bartlett, Starr moved his blacksmith operations, Starr & Peden, to Washington Street. This new location was also close to his house on Green Street. In 1882, the Starrs sold 197 Green Street to William J. Miller, who in turn sold the house to James A. Dixon a week later.

By the time the Starrs sold the house, Green Street had become an active business district. By 1885, commercial development had taken over most of the land on the eastern side of the railroad. The type of housing along the street had changed as well. “Multi-family dwellings made up nearly half of all residential property on Green Street in 1898 whereas, in 1874, there were only two multi-family dwellings on the entire street.” (Stiles, 2001) This change in housing was a response to a dramatic increase in population. “Between 1850 and 1900, Jamaica Plain’s population increased from 2,730 to 32,750.” (Stiles, 2001)

The story of 197 Green Street is an integral part of the history of Jamaica Plain. The house appears to be our only remaining connection to the area’s first development as a suburb and home for middle-class tradesmen – after the time of farms and country estates but before the introduction of multi-family dwellings and major business and industry along Green Street. The house illustrates both the rural ideal of the time period and the origins of the residential construction we continue to see today.

Footnotes

(1) Because of the age of the house, there are no existing blueprints. This poses a challenge in determining the identity of the builder or the original design. However, the architecture of the house as it exists today does provide clues to its age and the type of professional that would have constructed it.

(2) Deeds from that time mention the existence of willow trees in the area.

(3) Moses Hemmingway’s Farm Account Book (1844-1846), archived at the Massachusetts Historical Society, documents how in 1844 Belford and farm foreman Hemmingway frequently obtained manure from Abel Green for use on Codman’s pasture across the street and for use on Codman’s School Street farm.

(4) The history of 197 Green Street introduces us to individuals whose names are recognizable in streets and landmarks in and outside of Jamaica Plain – Peter Parley, Green, Jackson, Codman, Amory, Bartlett, and Starr. Considering the house’s proximity to the locations that bear their names, it is possible that there are connections between the people and the landmarks, though further study would be needed to bring connections to light.

This article was first published on the Jamaica Plain Historical Society’s page and is republished here with the author and JPHS’ permission.